Umiama 2019 catalogue essay

Professor Pat Hoffie AM

The oldest collection of Japanese poetry, the Man'yōshū, was composed during the Nara period. Compiled in the eighth century as a book that (some scholars argue) was meant to last for all time, the Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves contains a homage to the Japanese Ama, the wandering clan of women who made their living diving for shellfish, lobster, octopus and pearls. The women’s skills are legendary – able to hold their breath for up to two minutes as they free-dived deep in their search for the sea’s bounty, armed with little equipment beyond their courage, skill and the companionship and care of their ‘sisters’.

Over time these capable, resolute, highly capable ‘women of the sea’ traded in their peripatetic life to settle in fishing villages, but over the centuries the numbers of women working in this renowned and dangerous way gradually depleted. By 2014 their number had plummeted from an estimated ten thousand (in the years following WW 2) to an entire population of only two thousand along the coastlines of Japan.

In April 2019, Australian artist Zoe Porter returned to Japan, this time to take up a residency in the Toba-Shima region, an area famous for the increasingly rare continuing traditions of its Ama divers. During Zoe’s previous residencies in Japan she had researched the pantheon of hybrid human/ghost creatures that continue to flit in and out of daily experiences in Japan, just like they did in the past.

Her former residencies produced a wealth of imagery, many of which were composed of, from and into book form, a fitting outcome in a country where books are revered. The Japanese love of poetry and writing first made evident in the Man'yōshū has continued to the present, and over the centuries the people and creatures, the places and spirits and dreams and predictions and predicaments depicted back then have woven their way into a rich fabric of tales that connect the past to the present. The hybrid nature of many of the creatures in such imagery appealed to Zoe’s ongoing research interest in the shifting states of physical beings. Her focus on the transmogrifications of beasts into humans, of monsters into men, of spirits into material form has long provided subject matter for her art practice.

And in this most recent series, the book again features as an accumulator, recorder and preserver of a trove of unlikely data. Fish forms and sea creatures, patterns and wave rhythms, monstrosities rendered semi-familiar, strange accoutrements and weapons, tools and unlikely jewellery, portraits of the faceless are all captured from page to page in a compendium that convinces us that, in the hands of the artist, impossibilities are capable of being re-ordered into the stuff of our shared collective strangeness. The stark reduction of these monotones pushes the rhythmic insistence of the marks and lines, the pools of form to the fore as effortless syncopations of communication. As such, each page is rich with a lively energy that runs like a wordless current throughout every little publication.

It is also appropriate that Zoe Porter so often chooses watercolour as one of her preferred materials; its capacity to bleed into the very fibres of its substrate - to run and leak and seep and flow ‘til it takes on fugitive forms – evokes the fluidity of the personages that are the subject matter of so much of her work.

In this series she has also developed her book forms into a series of small folded structures that evoke the Ukiyo-e screens of Japan’s Edo period (1615-1868). The images on them described ‘the floating world’ portraying the daily life of ordinary people. References to this history have been transposed by Zoe Porter into new, overlaid composite narratives; ones where figures in states of becoming tumble and toss between currents of pattern and skeins and ropes of inter-connectedness. At times they seem held under, on the point of drowning in the flow of colour and form, only to emerge elsewhere transformed by the sea-forms into which they sometimes merge.

There are no surprises in Zoe Porter’s choice of the Ama as subject matter: the commanding, strong and sensual presence of these women is compelling; their close understanding of their environment is inextricably linked to their welfare and their precarious safety, and their carefully balanced skill-set includes fortitude, endurance and close collaboration. And, importantly for Porter, the mythology that has long surrounded them is plaited through with other imagery – those of the ningyo - mythical sea-creature-women the sightings of which go back to the earliest written histories of Japan. Such images belie terrifying creatures, shape-shifters that strike fear and horror rather than the seductive grace that’s come to be associated with the sea-sirens of western mythology.

In this new series Porter includes videos and photographs of other kinds of shape-shifters – women-creatures who lurk on other kinds of borderlines and liminal zones – who haunt the crepuscular edges of suburbia and prowl the borderlines of imaginations. For Porter also chooses to work collaboratively in recorded immersive performances that are re-tuned to the specifics of each of the places in which they are staged. Typically, too, this exhibition includes small artefactual sculptural forms that may or may not have been used by the creatures she paints in her imagery. Through such inclusions the artist toys with the divisions between the rational data of museology, science, artefactual evidence and the imaginative playgrounds of art and performance. Her reinterpretation of Ema Votive Plaques compound the blurring of such boundaries even further. Borrowing from the small traditional wooden plaques placed as votive offerings to the gods at Shinto shrines across Japan, the artist’s small sculptural forms are offered as respect to the vanishing life-practices of the Ama, to all the monsters and creatures and marine life of the sea, and to the sea itself.

Compelling in their fragility and attention to detail, these works are a homage to the Ama, to the fragility of our oceans and to the kinds of cultural practices that have revered and sustained our relationship to such places for centuries.

Radio National/ABC: The Art Hub with Eddie Ayres 31st January 2018

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/the-hub-on-art/the-art-hub,-weds-31st-january/9374850

Zoe Porter

Onespace Gallery

Penumbra

I once described Zoe Porter’s work as “a blending of Surrealist counterculture, Mad-Max-wasteland-chic, and prog-rock assemblage…the language of a civilisation reframed by anarchy and apocalypse”.[i]Since writing that statement years ago, I have observed that Porter’s work has developed a subtler character. Where once her performances and sloshing drawings would crash into the audience (sometimes literally), they now possess a sense of coolness and contemplation. It is apt that the title of this show isPenumbra. As any good student of painting or drawing knows, the penumbrais the gentle dissipation at the edges of a shadow. It is not the black centre (the umbra), but the diffusion of the shadow into nothingness. Although there remains a dark core in Porter’s work, her recent output leaks out of the long shadow of Marlene Dumas, Francesco Clemente, Odilon Redon, Wangechi Mutu, and the 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, and more [ER1] provocatively plies its soft edges. To return to the practical application of the term, penumbra has become almost epidemic with the advent and accessibility of digital painting programs and 3D rendering software. Whereas artists once used the technique strategically to indicate the elusive character of light in a work, digital artists working today apply the effect universally, so that every surface has the smooth, artificial complexion of an airbrushed peach. By re-deploying a term that has been unfortunately mothballed (along with observational drawing), this show firmly declares its studio craft bona fides.

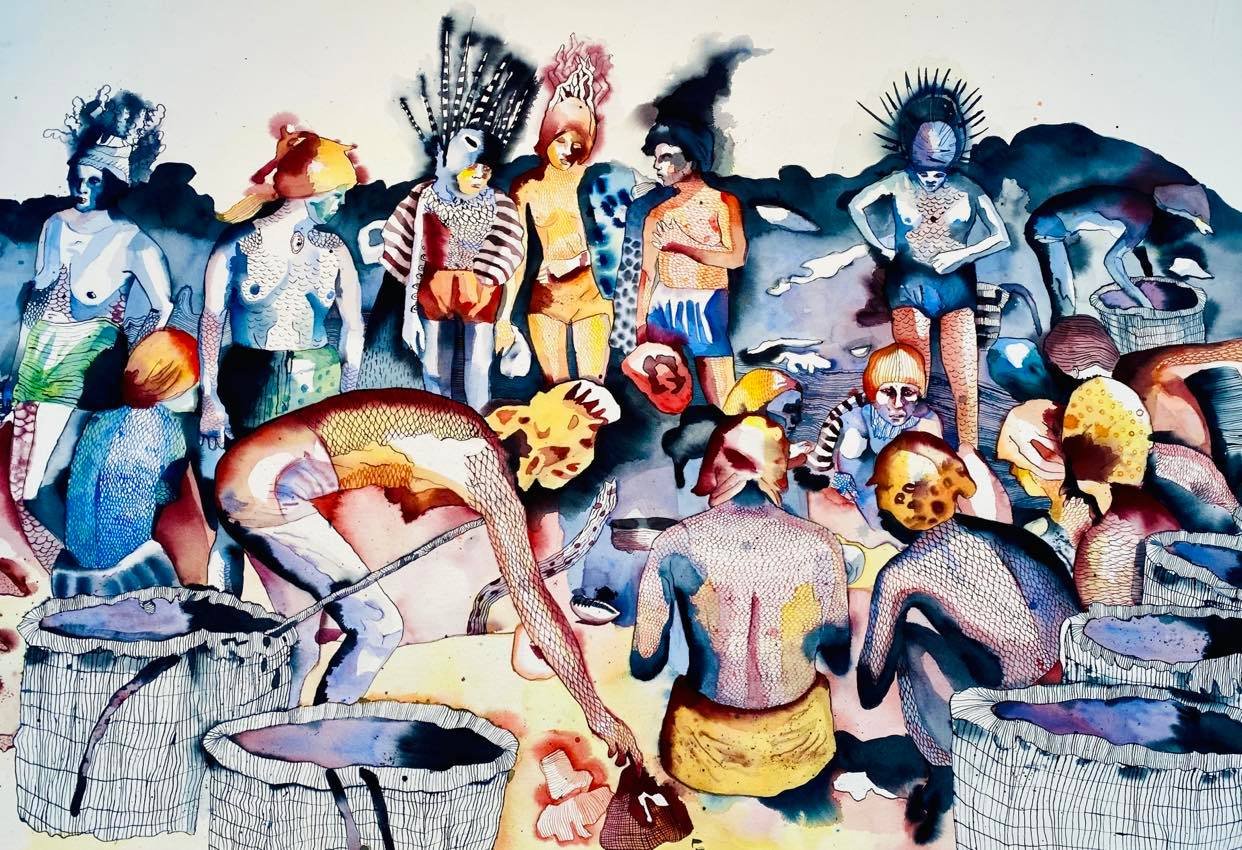

Persistent in Porter’s work is the presence of bodies. Bodies draped and wilting. Bodies disorganised and disoriented. Bodies larval and cryptic. In her own words, the artist asks that we put ourselves in a mind of metamorphism, zoomorphism, and anthropomorphism. Perhaps these bodies are arrested and depicted in a state of becoming, but perhaps they are also in a state of dress and undress, continually in the process of putting-on-and-taking-off-and-putting-on the performing objects that animate them (and not the other way around). It is important here to acknowledge the seductive phrase ‘performing objects’ coined by Frank Proschan in his semiotic analysis of puppets, masks, and ritual objects. Proschan defines performing objects as “material images of humans, animals, or spirits that are created, displayed, or manipulated in narrative or dramatic performance”.[ii]Porter’s work is a deep and elaborate excavation and examination of the limits of the performing object and its relationship to its attendant body. I have had the privilege of spending time in the artist’s studio and participating in her studio process. I have witnessed her patient and relentless method of assembling objects, swathing the body, acting and enacting, dismantling, reassembling, shedding, gathering, and destroying. Porter’s performing objects begin studio life as boxes and crates of flotsam and dross—poly-fill, felt off-cuts, tattered backdrop paper, tangled skeins of yarn, bargain-bin books, packing material, and anything that the op shop deems unworthy of its limited shelf space. When all this chaff intersects with the artist’s bodies, however, it becomes an animating force capable of making bodies perform (strangely).

My first experience of Porter’s work was not witnessing her loud and dark performances, but rather viewing her works on paper. I have clear memories of the artist’s studio papered from floor to ceiling with drawings and collages. The scale veered wildly from tiny characters drawn in the margins of books or on pages torn from magazines to mural-sized ink drawings that covered entire walls and spilled onto the floor. In all the works on paper, Porter fashions, re-fashions, nurtures, and abandons an ever-expanding menagerie of performing objects and their bodies. In one drawing, the body may be inflected by an odd set of pointed fingers or a pair of feet-turned-claws, and in another the body may be completely absorbed and reconfigured by its performing objects so that its coherence is lost. In every drawing and collage (with the exception of a few of the erotic watercolours), the body presents itself to the viewer as a vehicle of display and expresses nothing so much as genuine bewilderment that it’s being watched.

This latest exhibition by Zoe Porter is an excellent representative selection of her large body of work. The performances, collages, and works on paper are all present and demand of the viewer a patient attention that reaches beyond the polychrome phantasmagoria and into the peculiar-familiar space at the margins of the shadow and on the boundary of body and performing object.

William Platz

[i]William Platz, “Posing Zombies: Life Drawing, Performance and Technology”, Studio Research Journal no. 3 (2015): 44.

[ii] Frank Proschan, “The Semiotic Study of Puppets, Masks and Performing Objects”,Semiotica 47 (1983): 4.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Zoe Porter: Collaboration & Kinship (Carol Schwarzman)

https://polycentrica.com/2017/05/28/zoe-porter-collaboration-and-kinship/

2016 Anomalies: Solo Exhibition l Zoe Porter, exhibition catalogue essay by Alicia King

Much of nature engages in the curious phenomena of camouflage, blending invisibly with the environment. In 1935 an intriguing theory of animal mimicry was published by social anthropologist Roger Callois. Callois found some insects that camouflage with their environments do so for means beyond survival, as their predators hunt via scent. He posited their behaviour as a psychological adaptation to their environment - acting out a subconscious desire to dissolve physically and psychologically into surrounding space. This sentiment echoes vividly in the interdisciplinary practice of Zoe Porter.

Porter and her subjects meld into the layered scenes she creates. As spectators, we are drawn into a dream-scape where nondescript creatures inhabit spaces beyond conscious sight. Flickering across differing landscapes, realities, and eras - the borderline of old and new worlds - there is an element of psychological archeology at work in Porter’s practice.

Within the microcosm of Anomalies distinct elements emerge. New watercolour drawings are inhabited by anthropomorphic figures that seem displaced, drifting between human and animal, place and statelessness. Like hybrids in a state of transformation, these fluid subjects merge in and out of their natural environments. They bring to mind the enduring human desire to free oneself from the realities of humanness and become animal, and in this way invoke a primal relationship to nature - a now almost mythological space for humans to occupy.

The cluster of images In The Studio (series) blend layerings of reality and dream-like imagery through the manipulation of figurative photographs. Printed onto watercolour paper the images are then manipulated with watercolour inks, almost disguising their duality as the images merge into one. There is a sense of playful yet powerful exploration of female sexuality, and through it a metamorphosis of complex identities. Porter’s use of found-objects including LEDs and anatomical forms in sculptural works Anomaly 1 and Anomaly 2 are driven by a Surrealist bricolage method - a kind of stream of consciousness approach to making that is manifest in the exhibition’s entirety - a projection of Porter’s aesthetic stream of consciousness.

At Strange Neighbour, a live collaborative cross-disciplinary performance with Olivia Porter evokes a dark, almost freakshow-like interaction, conjuring the audience from an otherworldly place, as if dis/connected to the performance space via a slippery parallel plane. The performative landscape alludes to a mischievous Gothic conception, further strengthened by video piece Homunculi (Transmutations) showcasing the performer in a solo setting.

Porter’s live drawings have a detached sense of automatic writing about them, as if channelling elements of psychedelic nature and mysticism. I’m reminded of Marcus Clarke’s writing of the monstrous Australian bush, that in it “alone is to be found …the strange scribblings of nature learning how to write”. Here, drawing is a mercurial narrative that brings life to the creatures inhabiting Porter’s work. Lines escape their expected confines, confusing the boundaries defining space as complete or resolved, and in this way illicit an atmosphere of non-stasis; an ever becoming, overlapping, continuum of activity. Objects and studio remnants present in the performance also amalgamate to form the post-performance space, creating a strange and transitional, interdisciplinary space. Imbued with a curious, charged energy, the post-performance space acts as a remnant of a ritualised atmosphere, suggesting rhizomatic possibilities of transformation.

2016 ZOE PORTER: HOMUNCULI, exhibition essay by Alexander Kucharski

Her first solo exhibition in Brisbane since graduating with a Doctorate of Visual Arts from the Queensland College of Art, Zoe Porter’s Homunculi is as interdisciplinary as the Brisbane Powerhouse itself. Collage, drawing, mural, painting, performance, sculpture, sound, and video combine under a cohesive aesthetic to profile people—Porter herself, family, friends, and abstract hybrid forms—but as characters in scenes, not portraits. Porter’s pervasive colour palette and mark-making reflective of performative movement are common threads in this diverse body of work, thematizing activity, theatricality, and speculation.

Sister Olivia Porter is featured prominently in multiple works. A Circus Oz performer, Olivia’s movement is corporeally manifest in the opening night performance, explicitly captured in Porter’s video collaboration Transmutations[1] with Brisbane filmmaker Ali Cameron, and implicitly rendered in Posca Pen mural Urban Mythologies,[2] as well as a number of hanging works. Her movement, not quite dance yet not quite theatre, is emblematic of the hybridized forms she is represented as in ink and watercolour across multiple works. These paper compositions also depict, in different degrees of transformation, Brisbane (and ex-Brisbane) artists and friends Christian Flynn and Arryn Snowball, among other unidentified and imagined characters.

Porter’s use of the likenesses of her friends and family is, however, no different to her treatment of fictional entities. Both groups are surrounded by abstract scenery or objects out of scale, or are in a visual conflict for attention with other characters in the same work. Sometimes, the identity of the characters seems far less important than the overall composition of the image, as in, say, Grotesquerie, in the Visy Foyer. Sometimes, the identity of the characters is all you can focus on, as in Desert Camp,[3] where the birdman’s resigned posture poetically reflects his apparent refugee status, as a function of his surroundings.

Urban Mythologies, perhaps the most unique work in the show, stylistically refers to street art, through Porter’s application of the paint pen and use of patterned strokes to create depth in the absence of colour. Her sister stands in the centre, surveying objects and symbology that juxtapose the natural and the man-made: the Waratah and the commercial waste bin. Behind the scene is a tail (or snake-like appendage) attached to another Olivia, a surreal self-reflection on the character’s part.

This work serves as a useful, site-specific centrepiece for the exhibition, providing examples of the iconography present in the body of work as a whole. Its comparative and questioning narrative is evident in the expressions and situations that many of Porter’s characters find themselves wearing and placed in, and its mixture of patterned shapes, botanical forms, and animal fusions is a summary of her visual motifs.

The animal to Porter is the subconscious, the creative, the other. As a concept, it is integrated with Porter’s characters to varying degrees. Some are humans with animal attributes, while others take on animal postures or are in fact better described as humanoid creatures. Similarly integrated is the theatre of the carnival, including its costumes, symbolism, and detachment from ordinary life. These two subjects pervade the work, with comparable effect. Both are relatable metaphors for instinctual behaviour: existing outside the boundaries of anthropogenic societal order.

Accessing this idea in reverse is sculpted piece Trickster (Marsupial),[4] who in the context of the exhibition is anthropomorphized, a ‘roo with little suggestion of humanity bar his crown and the elevation of animal attributes to potent metaphor for human behaviour in the surrounding work. His downward, serious gaze belies his aggressive, but ultimately a little silly, headdress. He hides behind its venerable and regal quality, though it truly harbours his capricious and roguish personality.

The duality presented in these works asks more questions than it answers. Where are they? Why a washing machine?[5] But therein lies their beauty. Rather than relying on non-didacticism as their basis, Porter’s scenes explore questioning itself. Awash in dreamy backdrops and a playful interaction between the defined and the undefined, her characters face their audience, each other, their scenery, or somewhere beyond the limits of our view, irresolutely but calmly assessing. The mode of her performance drawing takes on this calm assessment as she responds to the movements of her co-performers, allowing the audience to access pictorially the inquisitive flow of their action.

Strikingly, just a few pieces feature collage, working away bits of scenery, salvaging other drawings, or more brutally transforming their subjects. This helps to remind the viewer of the indefinite nature of depiction, breaking the fourth wall to turn a moment back into a stage. In a performance space like the Powerhouse, it is relevant to question the nature of fictional representation and occasionally give the audience a glimpse of process before product.

Homunculi is expansive, organic, and thoughtful. It contrasts the utilitarian aesthetic the exhibition area cultivates, but remains internally consistent through its use of motif, subject matter, and colour, reflecting the multidisciplinary program of the Powerhouse as a whole. The expressive possibilities it encapsulates and champions are illustrative of Porter’s success in exploring multiple media, with no one medium triumphing over the others. Perhaps they got mixed up in the washing.

[1] Projected onto the Turbine Wall.

[2] Located on the back of the wall that runs through the Mosquito Foyer.

[3] Located in the Mosquito Foyer.

[4] Located in the Visy Foyer.

[5] See The Misplaced in the Mosquito Foyer.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Bête Noire: Solo Graduate Exhibition review by William Platz

Zoe Porter Bête Noire at The Hold Artspace

Review by William Platz July 2013

It may be elementary in discussions of performance art to observe that the lines

between document, recording, artefact and event have been hectored to the point of

piteousness. Zoe Porter’s exhibition at The Hold Artspace does little to crystallise these

muddled discourses, but her elegant installation of framed and unframed drawings,

snapshots, digital prints, drawings, ephemera, op-shop bricolage, extravagantly

costumed mannequins, and loud, dark video projections of past performances present

an exceptional case study in liveness and performance drawing. Porter’s work is

precariously balanced on the edges of object, drawing, costume, performance and

video. Tension abounds in her work, and far from the contrived novelties of so many

emerging artists, Porter is able to sustain a deeply peculiar method and iconography.

In one potent montage, a page from A Man For All Seasons with an ink drawing of a

zoomorphic desk chair (hooves, a striped tail) is pinned beneath a yellowed page from a

kanji primer on which an ink drawing of an imp with a large mask and a short spear

hunts a little triangle. Both hang beside a dense black and white photograph from one

of Porter’s performances. This small passage encapsulates the passages—martyrdom,

metamorphosis, wildness, mistranslation, absurdity and playfulness—in which the work

finds its fullest voice. It is in many of these small drawings, absorbed in their own little

constructed worlds of fantasy and detritus, that Porter’s aberrant menagerie seems to

thrive.

It has become commonplace to view an exhibition that comfortably quotes from the

infamous 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme while simultaneously indulging

the smooth and well-lit confines of the contemporary art gallery. The subversive legacy

of the 1938 Surrealist show, the Art of This Century Gallery and SI derivé are all brought

to heel in the interests of eye level, clear authorship and effective circulation patterns.

Viewers familiar with Porter’s work may be surprised by the formality and stillness of her

current exhibition. As a performance artist, Porter stages lush, sonorous

performances— combinations of performance drawing, improvisational theatre, jam

session and circus act. She deftly weaves an intense spectacle of the act of drawing.

The zoomorphs, zombies and chimeras that populate her drawings literally crawl about

the gallery, bang drums, paw at the audience, and shred heavily amplified and distorted

guitars. Porter, present in all her videos, is mesmerising as she utterly disregards her

audience and the other performers. The intimacy, aggression and anxiety of the

performances dissipates immediately, however, in the clean confines of the large gallery

that houses her mannequins, drawings and photographs. Perhaps ambivalence about

the relationship between performance and document/artefact is indicative of a larger

theme that manifests in the exhibition: the efficient bundling of an inefficient, irrational

and wonderful practice. The exhibition draws heavily on the work of Ernst, Masson,

Ubac, Dali and Schiaparelli, and just as those artists and the exhibitions they staged

have been neatly processed by the conservative apparatus of contemporary art

markets and scholarship, perhaps Porter’s work points to the inevitability of rigid

screens, text, white walls, d-rings and postal standards taming every wild thing that

manifests in radical performance.

Published online: http://zoeporter.tumblr.com

---------------------------------------------------------------

POSING ZOMBIES: LIFE DRAWING, PERFORMANCE & TECHNOLOGY by William Platz

Performance, the Body and Time in the 21st century

26-27 June 2013

Hosted by: exist

William Platz, PhD (Griff), MA (Excel), BFA (Pratt)

Queensland College of Art, Griffith University

Bio:

William Platz lectured in drawing and art history for over a decade at the Southwest

University of Visual Arts in New Mexico before immigrating to Australia in 2009. Dr. Platz

currently lectures at the Queensland College of Art, exhibits with the International

Neosymbolist Collective and publishes on the topic of life drawing.

Posing Zombies: Life-Drawing, Performance and Technology

Abstract:

This paper uses the metaphor of the zombie to instigate a radical alteration of perceptions and

practices of life drawing. Shifting attention from the conservative artist/model dyad, the

zombie is used metaphorically to interrogate posing, performance and action in the life

drawing exchange. Life drawing is a critically under-examined area of practice and pedagogy

and demands specific strategies to reform and re-position itself as a vigorous contemporary

form.

___________________________________________________________________________________

POINT TO POINTS by Professor Patricia Hoffie 2013

Exhibition Catalogue Essay (segment)

Point to Points

In this age of technological travel there’s more than enough cues and clues about ‘elsewhere’ to satisfy the curious. You don’t have to travel to experience the sense of difference. You can eat at any number of sushi bars right along the South Bank strip, then check in to a karaoke session socially lubed with sake and after that watch Japanese manga online or in cinemas. In Tokyo you can have your choice of kangaroo or emu steaks, buy drizabones and Akubras at specialty shops, and check a selection of Australian films online. So what is it that drives artists to get on a plane, loaded up with the luggage of their own art work, just to travel nine hours to put up an art exhibition in the name of an ‘exhibition exchange’? What is the point of it all? I asked myself that question when the eight artists in this exhibition arrived at the Queensland College of Art on the morning of an unseasonally stinking hot day after travelling all the way from Tokyo with their artwork simply so that they could take place in an exchange exhibition with six QCA artists.

But the answer’s an easy one – especially for artists. As practitioners trained to know that materials and place and timing are crucial, they know that ‘being there’ is a whole lot different to sending images through online processes. They well understand the point of taking the time to travel in order to connect all the other points together.

This exhibition is an example of what happens when artists start engagements with ‘elsewhere’: the experience grows like a rhizome and pops up again and again in different locations in new permutations.

The original proposal for this show sprung from an idea by Isao Yamaguchi, an artist who spent six months of his Doctoral studies enrolled at QCA. At that time, an exchange program with Queensland College of Art, Griffith University and GEIDAI (Tokyo University for the Arts) had established a pattern of reciprocal residencies where individual students from each university benefited from spending time at the overseas campus of the other. Since then Yamaguchi-san has completed his candidature, and for this current exhibition he invited other artist colleagues from Japan to join in with selected postgraduate students from QCA to engage in what is a fairly broad curatorial overview. However, broad though it may be, in the work of each of the Australian artists included there is a sense of possibility of at least two perspectives- two points of view - on the subject of their work.

Australian artist Zoe Porter spent four months in the QCA/GEIDAI exchange, and her series of works for this exhibition was produced during that residency. Zoe works across a range of media and genres that include performance painting and video, and her tiny assemblage in this show attests to core values in her broader practice. In this work she uses pages from old books sourced in Japanese antique shops over which she has painted shapes that evoke monstrous forms that are partly reminiscent of the ghost characters in Japanese anime and marsupial hybrid forms from the antipodes. In between these frames are images that relate to her performance work in which humans transform into other species and back again. Together they work to create a dream-state where the objects of everyday reality continually morph and flex into new forms.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Conjure: Zoe Porter Level Gallery, Brisbane 12 March – 1 April 2011

CARMEN ANSALDO | REVIEW: Artlink Magazine 2011

Zoe Porter's latest performance installation sees her previous drawings and paintings extended to realise a grander, more interdisciplinary environment. Featuring painting, music, video, acrobatics and pre-recorded soundscapes, Porter draws together several concerns regarding the relationship between the human and the animal in order to engage with a site-specificity which is simultaneously surreal yet uniquely Australian. The extension of her works on paper into both the third dimension and public space have allowed her to articulate a more elaborate vision of her investigations into the relationship between art, nature and the politics of place. She achieves this through references to the Australian bush, scattered throughout the painted and collaged figurations of the installation which introduce the viewer to her anthropomorphic transformation during the accompanying thirty minute performance.

Donning a costume evoking a marsupial-like creature, Porter plays handmade instruments, paints directly onto the gallery walls and interacts with her two similarly costumed, nameless accomplices in order to utilise all parts of the installation as a kind of landscape. The remains of the impact these characters make upon the gallery - instruments, amplifiers, paints and sheet music, form the basis of the installation for the duration of the exhibition. The accompanying video footage projected onto the wall adjacent to the performance feature the shadows thrown by a man dancing in a public park, elusive and mutable.

The open-endedness of the relationships established between the viewer, Porter and her anthropomorphic conspirators during the performance-event opens up new possibilities for imagining place and our impact within it. She poses these possibilities through the potential for audience participation via acts of creativity in public space, of which the man featured in her projection is an example. Her decision to leave the debris of the performance within the gallery space leaves open the potential for further ongoing collaboration through the audience’s involvement with the work in progress.

The surreal anthropomorphic beings featured both in the performance and painted aspects of Porter’s installation sit on the crossroads of her artistic concerns. Not quite human yet not animal, they often appear to be in shamanic states that are familiar to the viewer due to their usage of Australian iconography while simultaneously alien due to their discordant, semi-conscious nature. In the performance of Conjure, these beings struggle to articulate a world in which the role of the artist functions as a conduit, transporting the audience into surreal situations evoking the Australian landscape.

Porter’s past works found audiences at music festivals, cultural exchanges and street corners, sites that better suited her refusal to allow completion or closure in preference to considering her practice as an ongoing exploration. In this new work the 'relics’ she has consciously left behind from these endeavors - painting debris, stencils, stickers - trail back to the gallery. Her inclusion of sheet music, instruments, dance, light and smoke machines into the performance also demonstrates her unwillingness to categorise her practice into a tidy genre.

The staging of the work in the large front space of Level Gallery suggests an imagining of place which could be easily contextualised as a new genre of three dimensional landscape painting. This constructed landscape evokes Australian flora and fauna in a way which extends beyond simple interpretations of national identity towards a more complex and ambitious consciousness of place. The dualities of private and public, flatness and dimensionality, dreams and reality allow Porter and her collaborators to create interpretations which go well beyond any tired artefacts that might shape the dominant imagery of more standardised interpretations of ‘Australia’.

Thus we can see a post-colonial tendency at work in Conjure which disavows the notion of a grand narrative of nation in favour of a more flexible, ambitious reconstruction. By engaging with post-colonial theory by way of the surreal, Porter’s interdisciplinary landscape considers notions of territory, both animal and human, to suggest the parameters of a kind of dream-world where the artist functions as a central visionary representing both nature and culture. The three collaborators who appear to be caught in a state of becoming between being drawings, animals or humans, make music, painting and gestures that offer a loosely choreographed means of interacting in this half-dream, half-real scenario. They invite us to do the same.

Carmen Ansaldo

____________________________________________________________________________________

UTOPIA/DYSTOPIA/DISTURBIA (Pat Hoffie, Ed.)

The Site Markers Project by Penny Smith

ZOE PORTER: STRANGE PLAYGROUND at Woodford Folk Festival 2009/10

Zoe Porter's mural Strange Playground was installed at the entrance to Penny Arcade. Built in two sections it served to mark the entrance to Penny Arcade as well as to define one of the busiest arteries through the festival that leads to The Grande, a major music venue.

On arrival at the festival, Zoe began the process of pasting her hybrid creatures along the wall panelling such a way that they appeared to carry out their disreputable pursuits oblivious to the crowd passing by on its way to the concerts. Mostly, it seemed as though the figures ignored the passers-by; some with their backs to the crowd, some playing with extended and heavily erotic tails, one perched on a string in solitary contemplation, watched over by a large crow. In this way the artist created another world where the onlooker acted out the role of the voyeur attempting to make some of imagery that, while immediately recognisable, suggested a perverseness that was unfamiliar and at the same time enticing. By introducing a number of other characters that appeared to stride in unison with the people walking the festival street and yet others cavorting in the same way as the street acrobats, the artist managed to blur the boundary between reality and her imaginary world.

Lessening the divide even further, Zoe's sister Olivia was introduced to perform her theatrical antics. For these performances, Olivia utilised hybridised bodily extensions and prosthetic costume pieces to emphasise a loosely choreographed series of slow, furtively erotic movements. Some of the figurative imagery for the paper cut outs was derived from photographs taken at the previous festival when Olivia performed in conjunction with an exhibition of Zoe's paintings that had been included as part of the Carnal Carnivale exhibition that was held in a gallery-tent erected at the entrance to Penny Lane. The resemblance of the miniature paper cut outs to Olivia's street theatre persona was disconcerting. As Olivia crawled and slithered against the wall, the boundaries between past and present, between performance and presentation, and between illusion and reality became even further blurred.

___________________________________________________________________________________

EATING BISCUITS...THOSE EVERYDAY SPACES WE OCCUPY

Written and curated by Dr. Debra Porch l 30 July -20 August 2010 l LEVEL ARI l Exhibition Catalogue

Zoe Porter - The Chimeras

I would journey out late at night with a bucket of sticky wheat paste, a large paint brush and paper cut-outs in hand gluing the animal/human hybrid creatures onto various abandoned buildings, alleyways and grubby walls throughout Brisbane..these dreamlike and otherworldly beings have taken on a different quality - removed from their normal studio context...they have become a part of the everyday environment.

These are Zoe's unique chimeras - part human, part animal, and mysterious and mischievous at the same time. Everyday spaces are transformed with the imagination of an artist.

Zoe's work occupies dual spaces, transforming the mundane into the memorable, the work is impermanent, and only likely to be visible for intermittent periods. Of course this comes with some aggravation as passers by, police and late night traffic are dodged in the process of working with the sites of her city environment. The studio becomes the street. The connection that is made again is between the viewer and the artwork. What is this particular duality that is exhibited - is it that the art is public and not permanent, or is it that each of us can see the invisible line between being human and animal? Or perhaps like Isabel Carlos, we have not yet found a vocabulary to talk about these connections:

It will probably take some time before we find the appropriate vocabulary to speak about the inextricable connection and interdependence between emotion and reason, between body and mind, human and nature; until we find concepts that reflect the purpose of those central dualisms in Western culture. (Isabel Carlos, On Reason and Emotion, 14th Biennale of Sydney, Biennale of Sydney, Sydney,2004).

I walk through the streets of the city, I look twice, my perceptions of place have shifted. Did I just see Zoe's body jumping out from that wall? No, it was one of Zoe's chimeras - and I smile.